Costa del sol bjuder på många dina utflyktsmål.

Läs om mina förslag på vackra bergsturer.

Välkommen till min webbsida som handlar om trivsamma platser i Europa, utflykter i Andalusien och sköna promenader i Stockholm.

Klicka på det som intresserar dig!

Trevlig läsning

SAINT EMILION

E5, A10, 26 km. east (north:exit 40; south:exit 26) /42 km/

Saint Emilion is an enchanting little town sitting on a horseshoe-shaped hill looking down on its riches. It is the centre of the wine district which bears the same name and is surrounded by vineyards and no fewer than 94 wine castles. This, if nothing else, is testimony to the wealth of the area. The wine castles start appearing along the road between the motorway and Saint Emilion, enticing you to pull in for a “degustation”. But do by all means also botanize in the country roads off the main road. These offer numerous opportunities for wine tasting.

GET YOUR SENSIBLE SHOES ON!

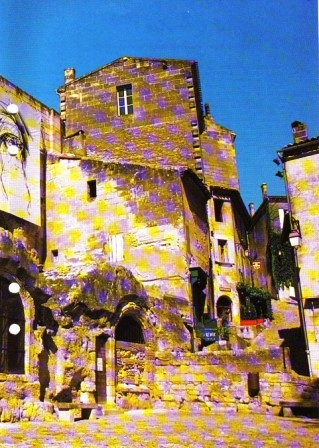

The town itself is well kept, gleaming like a precious piece of jewellery, and has a uniform and harmonious character. Nearly all the houses are built in a warm, golden local stone which gives a very special glimmer, especially at sunset. If you are planning to take a walk through the town, then dispense with your high-heeled shoes, because you will need sturdier stuff on these steep, cobbled hills. The prudent walker will hold on to the handrails which are conveniently placed at critical points.

“THE CAVE CHURCH”

In the centre of town lies Place du Marché with a most remarkable church, dug out of the mountain, as is explained by its name, Église Monolithe. It is here that the town has its origins. In the 8th century a wandering monk by the name Emilion came to this place and made his dwelling in a cave. Emilion’s godliness attracted other believers and together they founded a Benedictine monastery. They widened the original cave in the porous chalk mountain and dug out further caves. Some of the cavities they used as their humble abodes, others for burial chambers. In the largest of the caves they held their divine services and decorated its walls with fantastic paintings which unfortunately, for the most part, have now disappeared. Little by little houses were built around the openings to these caves and a village grew up.

UNDER BRITISH SOVEREIGNTY

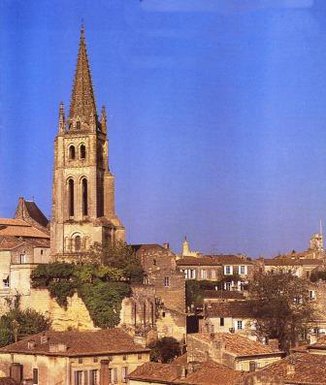

However, the hermit monks and the villagers were not allowed to live in peace for long. They were threatened from north and south, by Vikings as well as Muslims constantly on the rampage. It became necessary to build a stronghold, and in the 12th century the village was enclosed by a 2 km long stonewall with six gates. Of these gates only one, Porte Brunet, can be seen today, but fragmented remnants of the wall are still there. In the 11th century Saint Emilion was handed over to the English Crown and so belonged to the enemy, which brought both benefits and drawbacks. Benefits, because the English kings were so interested in the wines of Saint Emilion that the district was granted special privileges, such as favourable export terms; drawbacks, because the enemy was never far away. During this period with its reasonably fair political climate, many new buildings were erected. It was the monks who were the driving force behind this, and they built, among other things, a monastery complex with the diocesan church, Église Collégiale, in the Romanesque style of the 12th century. A Romanesque tower, rising majestically above the Cave Church, also dates from this period. Later, this tower was crowned with a Gothic spire.

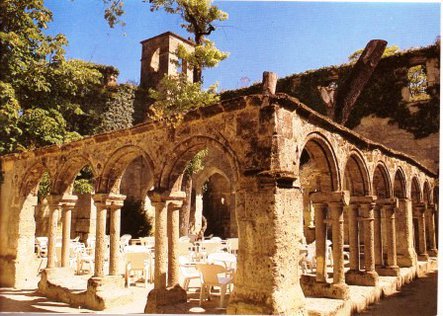

La Chapelle de la Trinité, the Trinity Chapel, was built in the 13th century in the immediate vicinity of the Cave Church and is an elegant example of High Gothic style. Henry III of England now also had a citadel built, Le Château du Roi, which today only consists of a tower. At the end of the 13th century there was no room for further buildings within the walls, so the monks decided to build a large monastery outside the stronghold. However, history shows that this was a foolhardy decision. The monastery was not allowed to stand for long, and today there are only a few ruins left, Les Grandes Murailles, in the middle of the vineyard, bearing testimony to the precarious living conditions in times gone by. In 1371 the monks built a new monastery, Le Convent des Cordeliers, this time inside the city walls. This monastery was given a longer respite and today we can admire its romantic ruins.

WAR AND CROP FAILURE THREATEN THE WINE CULTURE

The French naturally wanted to rid themselves of the English who were occupying what they saw as their own wine territory and in 1337 the 100 Year War broke out. It lasted, with some interruptions, right up until 1453, when Saint Emilion became French again. The war had catastrophic consequences. There were only a few hundred inhabitants left in the town, which lay in ruins, and to make matters worse the French monarch repealed the town’s privileges and banned all trade with England. The town recovered slowly, only to be plundered a century later during the religious wars. During the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the wines of Saint Emilion gradually gained in renown. More and more plateaux in the district were cultivated and the monks put in a great deal of work to clear new land for vineyards. This time more attention was given to the quality of the vines and the studying of grape varieties, soil and generally enhancing the quality of the wine.

Maybe it had been a mere stroke of luck when the Romans, as early as around 20 A.D., happened to come upon a strain of grape from what is now Albania which thrived in the soils around Saint Emilion. It soon became clear that the Saint Emilion wine production managed to hold its own in the wider competition. But in 1789 things took a different turn. The French Revolution had enormous repercussions. Firstly, “la Jurade”, the local government board, was abolished. This body of district rulers had been playing an important part since the 12th century and held responsibility for everything from tax collection to the judging of the quality of the wine. Moreover, the French Revolution led to the Christians being persecuted and their holy buildings looted. Many people were forced to flee their homes and the wine trade was soon reduced to a minimum. Then, in the 19th century, the wine trade was resumed and the railway system now facilitated transport. But all was not well: the vines were occasionally hit by various blights and pests and the two world wars of the 20th century caused serious disruption to the wine production.

A FLOURISHING WINE TOWN

Today Saint Emilion is a prosperous town which can look back on a distinguishable history and is able to offer its visitors a very pleasant stay. Here are plenty of cosy restaurants huddling in the steep alleyways, treating you to good food and of course the exquisite red Saint Emilion wine. If you are in the mood for some serious wine tasting you can hop on the little tourist train which goes straight out into the vineyards, pay a visit to the producers and sample the best wines grown there. Back in the town inside the medieval city walls you can easily imagine yourself in a bygone era, lulled to sleep by the flapping of the wings of history.

The town is surrounded by vineyards

Steep hills and weathered house fronts

The Gothic tower of the cave church rises high above the houses

Pleasant restaurants everywhere